From March 26…

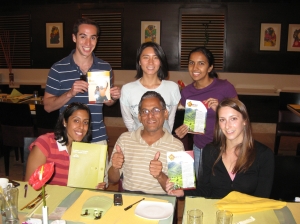

After a 5:45am wake up call to head to the airport, I am exhausted right now. I’m on the airplane from Hyderabad to Mumbai, but I can’t sleep. I keep thinking about the key lessons I have learned as a study tour as both an organizer and a student for the Agriculture in India trip.

Context: As an Indian-American, I have visited India often but had only lived here for 6 months in Mumbai before MIT. Through the lens of my classmates, I was the “expert.” I learned about the balance of what I could provide and what I could not provide my peers. How could I change the “expert” lens into creating a culture of many experts and knowledge sharing?

Perspective: Having lived in India, I also had the greatest understanding of the Indian perspective-from rickshaw drivers “knowing but not really knowing” how to get somewhere, to the language barrier of Telegu and Punjabi, to the need to “ask for a bill” or the culture to “not question” senior figures in certain situations.

This got me thinking: who really is the expert? Is it the 60 year old agricultural Indian scientist, the 40 year old farmer, the 50 year old prime minister, or the self help womens groups? This is why stating and reviewing assumptions is so important, because it all comes down to context and perspective.